AP Photo/Paula Illingworth

- On February 17, 1864, Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley attacked and sank USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor, killing five Union sailors.

- Hunley became the first submarine to sink an enemy warship, but Hunley and its eight crew members didn’t make it back from their historic mission.

- Visit the Business section of Insider for more stories.

On the night of February 17, 1864, US Navy sailors aboard the sloop-of-war USS Housatonic were watching the approaches to Charleston Harbor. They were part of the Union Navy’s blockade force, which was approaching its third year of operation outside Charleston.

At about 8:45 p.m., Acting Master J.K. Crosby noticed a large semi-submerged object slowly making its way toward the sloop. It was believed to be a porpoise or log, but as the object came closer, its size and metal body made clear that it was a man-made vessel.

The sailors raised the alarm, but the vessel was too close to be hit by the sloop’s 12 guns, forcing some of the crew to shoot at it with muskets and pistols.

But they were too late. The vessel was the H.L. Hunley, one of the first submarines in history, and the first to successfully sink an enemy ship – at the cost of the lives of its entire crew.

A desperate naval situation

American Civil War Museum

The Confederate States of America were at a naval disadvantage as soon as the war began.

The Union maintained control of virtually all of the US Navy's vessels and destroyed those in vulnerable ports in the South. The Union also began a massive ship-building program that would see its Navy swell from 90 warships in 1861 to over 600 by 1865.

Recognizing the importance of isolating the CSA from any foreign markets or assistance, President Abraham Lincoln ordered a massive blockade. By 1863, it had largely succeeded in cutting off nearly every major port along 3,500 miles of Confederate coastline.

The blockade had a devastating effect on the South's economy, which relied heavily on selling agricultural products, like cotton, abroad.

The Confederates built a very modest navy from scratch, and although some vessels became successful commerce raiders, it was nowhere near large or strong enough to break the blockade.

By 1863, the Confederates were desperate to end the blockade, going so far as to offer bounties for the destruction of blockading Union ships. They were forced to develop revolutionary new designs in an attempt to make up for their shortcomings.

H.L. Hunley and his submarines

AP Photo/Bruce Smith

Horace Lawson Hunley, a former deputy collector of customs in New Orleans and state legislator in Louisiana, recognized the importance of breaking the blockade early in the war.

In 1862, he and a small team built a small submarine called the Pioneer in New Orleans, but they were forced to destroy it when Union forces captured the city.

A second attempt, the American Diver, was built in Mobile, Alabama, but sank while being towed. Finally, in July 1863, Hunley successfully launched his third submarine, which would eventually be named after him.

The sub was made of iron and had the shape of a cigar with the front and end sections wedged. It was nearly 40 feet long and only 4.3 feet high.

It was powered entirely by hand, with seven men continuously cranking levers to move the propeller, while the commander steered and operated pumps for the two ballast tanks. Two small conning towers containing hatches were on either end of the sub.

AP Photo/Bruce Smith

After a successful demonstration, it was hurriedly sent by rail to Charleston in August, where the man in charge of the city's defense, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, wanted to use it immediately. Confederate defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg had increased the need for an end to the blockade.

But the submarine wasn't ready. By October, it had sunk twice during training missions, killing 13 men, including Hunley himself.

Beauregard began to lose confidence. "I can have nothing more to do with that submarine boat," he declared. "It is more dangerous to those who use it than the enemy."

But Beauregard was convinced the sub could still work by Lt. George Dixon, who raised a new crew and became the sub's commander.

A doomed victory

Bettmann/Getty Images

After its second sinking, the Hunley was forbidden from completely submerging. The plan changed from towing an explosive device under a Union ship to using a spar torpedo.

The torpedo, a 16-foot pole with a 135-pound explosive at the end of it, was attached to the lower bow at a 45-degree angle, and would be detonated on contact or by a trigger-pulled device.

After months of training, Dixon and his men were ready and waiting for a night with good weather. Their moment came on February 17. They left their base on Sullivan's Island and began their attack on the USS Housatonic at 8:45 p.m.

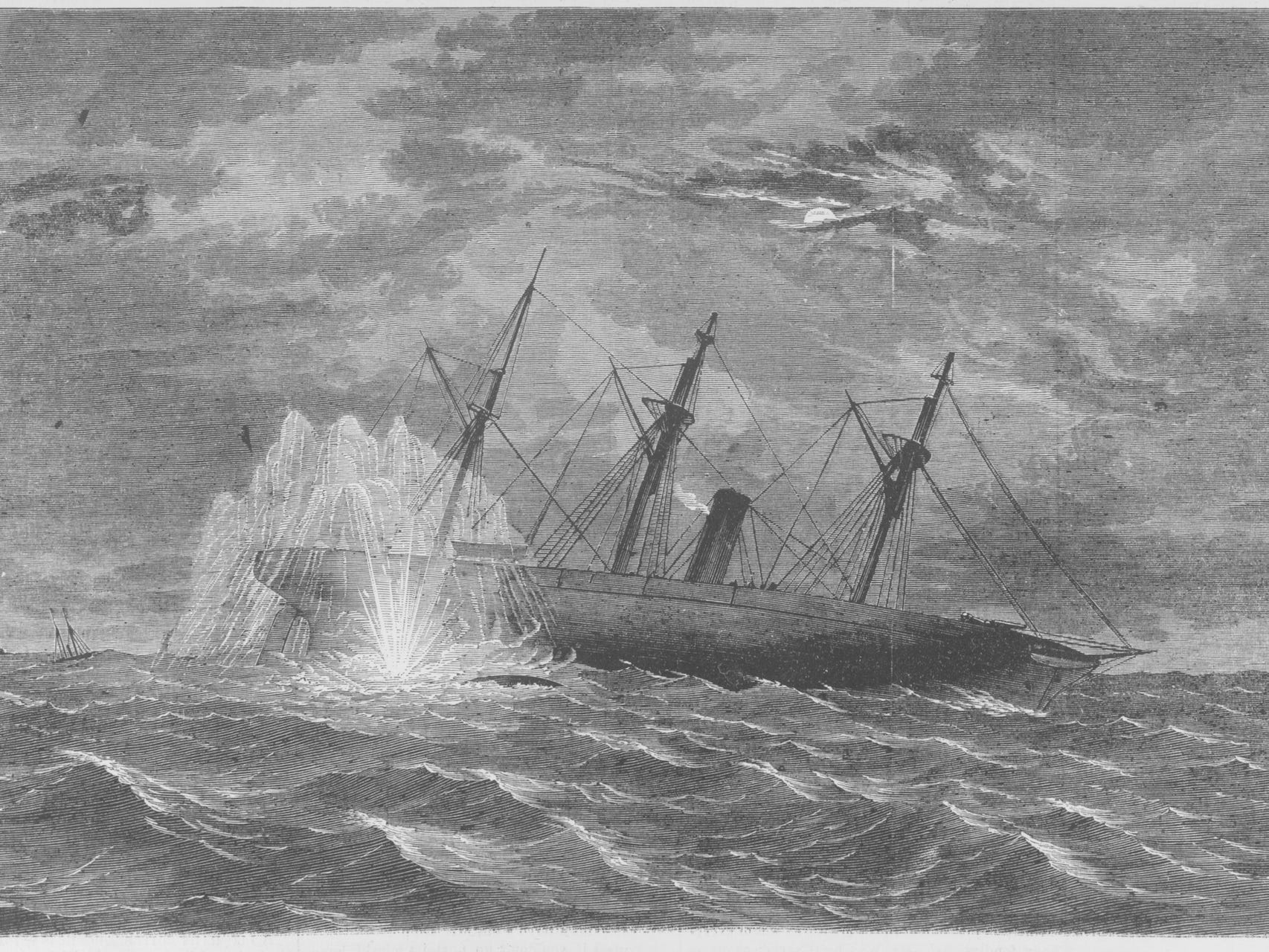

The small-arms fire failed to stop the Hunley, and its torpedo detonated shortly after it made contact near the rear of the sloop. The massive explosion tore a huge hole in the ship and instantly killed five sailors.

Within five minutes, the Housatonic sank. The rest of the crew survived by escaping in two lifeboats or by climbing the masts, which remained above the water, until they could be rescued.

The crew of the Hunley were not so lucky.

Eyewitnesses claimed that lights signaling a successful operation could be seen from the submarine. However, the sub never returned to Sullivan's Island. The Confederates never attempted a similar attack, the Union blockade was never broken, and the war ended 15 months later.

Rediscovery, theories, and legacy

Naval Historical Center

The Hunley was not seen again for 131 years, when a search party found it in 1995. It was raised in 2000 and placed in a tank at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where it is on display.

The cause of Hunley's sinking has never been definitively established. In 2017, a team from Duke University led by Rachel M. Lance, a biomedical engineer and blast-injury specialist, released a study arguing that the crew likely died instantly from air-blast trauma.

Lance, who wrote a book about her research, concludes that the pressure inside the sub from the blast "put each member of the Hunley crew at a 95% risk of immediate, severe pulmonary trauma."

The crew's skeletons were all found at their duty stations, with no signs of physical injuries, and not near the hatches, which were closed, suggesting there was no attempt to escape. There was also no damage to the hull that is believed to have caused flooding.

The Hunley's final resting place was also almost 1,000 feet farther out to sea than the wreck of the Housatonic, suggesting the submarine drifted with the current before sinking.

The H.L. Hunley was the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy warship, a feat that would not happen again until World War I.